You know, sometimes I take no pleasure in doing this. I hear the response, so why do you bother? Well, as I think I said, it’s pathological. Really, though, sometimes I turn up to a movie which is obviously gunning to touch upon some serious emotional issues, and take a stand against bigotry and prejudice, and leave the audience uplifted and positive, but as much as I’d like to say positive things about it, I just find myself bitterly regretting the fact that the re-release of Apocalypse Now was on too late for me to see it on a work night, and that one can only go and see Hobbs & Shaw so many times before it starts to look weird.

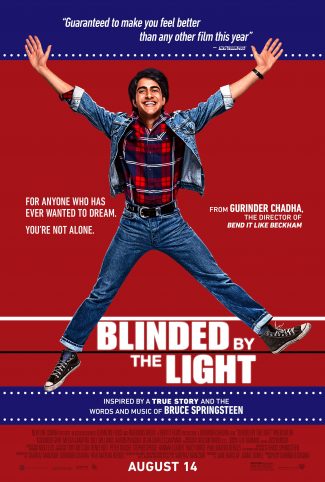

The film that has me thinking this way is Gurinder Chadha’s Blinded by the Light, a bildungsroman with music, and a film which seems specifically designed to put you in mind of other films you may have enjoyed in the past. Viveik Kalra plays British Asian teenager Javed, living in Luton in 1987 (he is basically a fictionalised version of Sarfraz Manzoor, one of the co-writers). Many films have been made about the travails of growing up as a second-generation immigrant in a fiercely traditional, patriarchal family, and we are surely overdue for one which approaches this whole topic in a wholly fresh and innovative way. Unfortunately, Blinded by the Light is not that movie, and we just get all the usual bits and pieces, from the strict, conservative father (Kulvinder Ghir) on down.

Well, Javed goes off to Sixth Form College where his inspiring English lit teacher (Hayley Atwell) soon spots he is a frustrated poet, but one with little chance of ever properly expressing himself given the way everything is in his life. It just gets worse as his father loses his job and the National Front seem to be on the advance. It all comes to a head on the night of the Great Storm of 1987, when he finally gets around to playing some cassette tapes a friend has lent him – they are, of course, two Bruce Springsteen albums, and Javed’s life is utterly transformed. Well, a bit transformed. Eventually.

I could go into more detail but the film adheres to the standard script-writing structure with grim fidelity: there’s a succession of alternately sad and uplifting bits, building up the stakes, then a really downbeat bit at the end of the second act, followed by a life-affirming climax where the protagonist gets a chance to show everything that they’ve learned about The Important Things in Life. In this respect, like many others, it does sort of bear a close resemblance to Yesterday, another film looking to deliver a feel-good experience powered by some familiar tunes. Neither of them really had that effect on me, though, although I must say that Blinded by the Light manages to make Yesterday look much slicker and better assembled than it does in isolation.

There is just something very odd and not-quite-right about this film. It’s supposed to be a paean to the power of the music of Bruce Springsteen… which is why the opening section is soundtracked by the Pet Shop Boys, a-Ha and Level 42. (I suppose the film-makers will say they’re holding back the Boss for the revelatory moment of Javed’s first hearing him.) But is it even that? (The paean, I mean.) At times the film resembles a bizarre mash-up of a jukebox musical using Springsteen songs and yet another comedy-drama about the Pakistani immigrant experience. This is an odd fit, to say the least: I know Bruce Springsteen has received many accolades, but I wasn’t aware he was acclaimed as the great interpreter of the British Asian experience in the late Eighties. Maybe the suggestion is supposed to be that his music has that kind of universal power and appeal – well, maybe so, but it still seems a very strangely specific take on this idea.

This is before we even get onto how the film handles its Springsteen tunes. When they do eventually arrive, they are initially accompanied by the words of the lyrics dancing around Javed’s head as he listens to his Walkman, which I suppose is just about acceptable. However, the writers soon decide they want to get some of the fun and energy of the non-diegetic musical into their film, so they break out a few big set-pieces. There are always choices with this sort of thing – you can keep the original Springsteen vocal and have the cast lip-synch to it. Or, you can re-record the song with the actors singing it (or attempting to sing it, if you’ve hired Pierce Brosnan) and use that. Or you can do what happens here, which is to play the original version and have the actors singing along over the top of it (not especially well).

If the singing is not exactly easy on the ear, it is at least better than the film’s attempts at dance routines. I would say these looked under-rehearsed, if I was certain they were rehearsed at all. The result has a sort of desperate earnestness to it which I tried hard to find charming, but I’m afraid I just couldn’t manage it. Something about the film’s biggest musical sequence (a version of ‘Born to Run’ performed in Luton High Street and just off the A505) not only managed to banish most of the vestigial goodwill I still retained for the movie, I’m also pretty sure I could feel it trying to suck out my soul and devour it. I’m not a particular Bruce Springsteen fan, but I can still appreciate the power and passion of his music – however, this film came alarmingly close to making me like his stuff a bit less. (A slightly bemused-looking Boss turns up during the closing credits, having his picture taken with various people involved with the production – one wonders if he was actually aware of who they were.)

That said, often enough they play Springsteen’s stuff without mucking it about or singing over the top of it, and this at least means you are listening to some great songs. This is better than the alternative, which is watching and listening to the scenes telling the story of the movie. These are – well, trite is one word that springs to mind. (‘Blinded by the Trite’ wouldn’t be a bad title for the movie.) None of the characters really behaves like a recognisable human being – they are all stock types living in a dress-up cartoon version of the 1980s, communicating largely in platitudes. Hayley Atwell plays the inspiring teacher, whose functions are to be inspiring and operate a few plot devices. Rob Brydon (wearing a truly shocking wig) plays a comedy relief old rocker, whose function is solely to be the comedy relief. It’s like the guts of the movie are on display throughout – it just doesn’t have the artifice or self-awareness to appear anything other than clumsily manipulative. (It could stand to lose about a quarter of an hour, as well.)

Of course, it does take a stand against racism, which of course is a good and laudable thing to do; and it does make some points about self-expression and being true to yourself and following your dreams, which are all perfectly good and admirable goals in life. Having good intentions doesn’t excuse the numerous narrative and artistic shortfalls of the movie, though. This just about functions as a story and as a musical, but it’s laboured and clumsy and trite throughout: all in all, rather more loss than Boss.