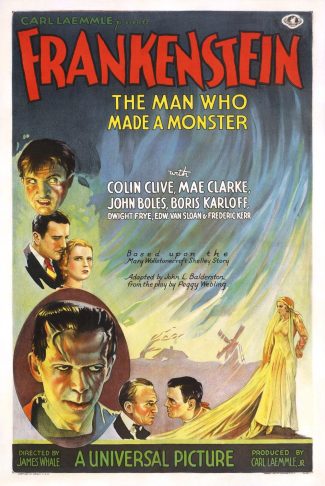

If you look back at the history of the horror movie, you can often discern lines of descent connecting different films, in terms of theme, influence, and personnel – what happens is that someone hits upon a popular template or formula and then exploits it to death over the next few years, with other people trying quite opportunistically to cash in on this. In the US, the success of Frankenstein and Dracula led to a whole succession of other films from Universal, with a cultural influence which lingers to this day, even if the studio’s attempts to exploit its back catalogue have been variably successful at best. Something similar happened in the UK with Hammer Films from the late 1950s onwards; in this case other studios were successful with their own variations on the Hammer style – tellingly, the iconic stars of the most famous Hammer movies were frequently cast by their competitors, too. Back in the US, the enormous success of Halloween led to the dominance of the slasher movie. More recently we have seen booms in torture porn, found footage and zombie movies.

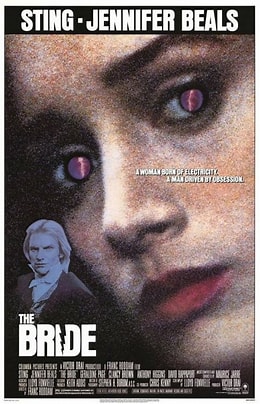

Every now and then you get a movie which doesn’t seem to be part of any particular line of descent – it appears from nowhere and then pops out of existence, usually because it wasn’t a success at the box office. With low-budget movies this isn’t unusual, of course, but for a fairly big film with well-known names involved it’s more surprising. Which brings us to The Bride, a 1985 film from the British director Franc Roddam. Roddam was also behind the movie version of the Who’s Quadrophenia and the 1991 bergfilme K2, but has really had more success creating and exec-producing TV series, his most notable success probably being Auf Wiedersehen, Pet.

The Bride is, as the title suggests, somewhat inspired by Bride of Frankenstein – moreso than the original novel, anyway, in which the bride herself is more of an idea than an actual character. If you wanted to be particularly generous to the film you might suggest that it’s a sort of alternate version of how the ‘canon’ novel ends. It opens, traditionally enough, on a dark and stormy night at Castle Frankenstein, where the Baron (Sting, who only gets the ‘and’ slot in the credits for some reason) is preparing to animate his female creation. The film’s tendency to go for surprising casting decisions continues as he is being assisted by one Dr Zalhus (Quentin Crisp, with purple highlights – it’s hard not to see this as a homage to the Pretorius character from the Universal Bride), while in the Igor role is a young Timothy Spall. Down in the cellar Frankenstein’s creature (Clancy Brown) waits anxiously, for she has been promised to him.

Yes, it’s an odd choice to start the story at this point, isn’t it? But then it’s a film full of odd choices, many of them based on the assumption that the audience is already familiar with this story. Perhaps this is why the film-makers also seem to be under the impression that the creation of the first monster has no dramatic potential any more, despite it being at the core of the story. It’s almost like they’re trying to do Frankenstein without doing Frankenstein, somehow.

Anyway, the bride (Jennifer Beals) turns out rather well, from a calligynic perspective at least, and almost at once you can sense Frankenstein (here given the first name Charles, even though Karl would surely have been the local equivalent) is starting to have second thoughts about handing her over. She certainly reacts with fear upon meeting her counterpart, which sends him into one of his moods and the ensuing scuffle sees the laboratory blown up, killing Crisp and Spall, and apparently seeing the demise of the monster too. This sequence sees some classic 80s music-video style special effects, classic 80s big hair on Beals, and a sort of grisly inventiveness (dismembered body parts twitching, etc) which is notably lacking from the rest of the film, sadly.

Naturally, he survives, and wanders off into the countryside, apparently aimlessly. On reflection, one wonders why: prior to the start of the film, he apparently had enough of a grasp on reality to understand his relationship with Frankenstein and enough nous to be able to pressure the Baron into providing him with a partner. But for the rest of the film he’s just amiable and naive, if not actually simple-minded. Anyway, in the course of his meanderings he meets Rinaldo (David Rappaport), a small-person trapeze artist on his way to join the circus in Budapest, and the two of them become friends. Frankenstein’s monster decides to run away and join the circus too.

Meanwhile, back at the castle, Frankenstein is wondering what to do with his latest creation, whose habit of wandering around the place naked outrages his housekeeper but probably keeps some undemanding audience members happy (it’s a sleazy scene, not helped by the way it’s been lit to disguise the use of a body double – the woman’s face is in shadow but as a result it looks as if a spotlight is being shone on the region below her waist). There are shades of My Fair Lady as the Baron resolves to help her pass in society, giving her the name Eva and beginning to teach her how to behave.

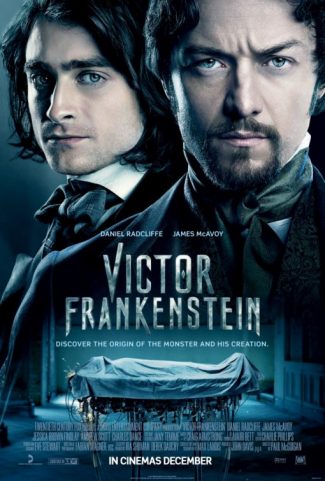

And we go back and forth between the two creatures and the people around them – Rinaldo gives the male creature the name Viktor (presumably this is why they’ve rechristened Frankenstein, as it’s his own name in several adaptations of the story), and they get jobs at a dodgy circus run by a money-grubbing Alexei Sayle in the ethnic scumbag mode that was the foundation of his career until Omid Djalili came along to relieve him. Meanwhile Eva causes something of a stir in her society debut, attracting a number of young men (a young Cary Elwes amongst them), and sparking a smouldering jealousy in Frankenstein himself.

‘A woman born of electricity – a man driven by obsession!’ declares the poster tagline for The Bride, somewhat excitably, the man in question being the Baron himself, of course. You could argue that casting Sting is a sign that the film is looking to go down the same Romantic route that Ken Branagh’s take on the story would follow nearly ten years later – he certainly looks the part of a brooding, poetic fellow, but the character is written with no depth or charisma, just a massive self-regard and sense of entitlement. Sting seems a bit at sea in the part, and the same could be said – charitably – of Jennifer Beals (a Razzie nomination was duly awarded to her). It’s not as if either of them ever do anything particularly interesting – the script seems to have put a big bet on the power of movie star charisma and crackling sexual chemistry where these two characters are concerned, which was a mistake, for the film just ends up with two good looking people in nice period costumes standing around acting badly at each other. (Also appearing in a few scenes here is Anthony Higgins, the only actor in the film with a significant Hammer horror pedigree, but he gets virtually nothing to do.)

Things are a bit better over in the storyline about Viktor and Rinaldo, mainly due to a winning performance by David Rappaport – the portrayal of the friendship between the two of them is the most successful part of the movie by a country mile, and Rinaldo’s departure from the story, though laden with pathos, is something that the movie has no chance of recovering from. Once Rappaport is gone the film becomes very dull indeed, despite the fact that this is when most of the action happens.

Most Frankenstein movies stand or fall on the strength of their ideas and the extent to which they find some new spin to put on Mary Shelley’s original ideas. One of the main problems with The Bride is that its only real innovation is to depict the relationship between the Baron and Eva as a kind of twisted, controlling romance. This might have worked with better actors and a better script, but as it is it’s overshadowed by the story with the circus – which is basically just a close cousin of Of Mice and Men, a verging-on-the-sentimental drama rather than anything with an SF or horror angle to it. It’s as if the film has emptied all the philosophy and horror out of the Frankenstein story and not found anything to replace it with.

The most striking element of the film, from a 2024 perspective, has nothing to do with Viktor the monster – but the storyline about how Eva slowly comes to realise her origins, and gradually asserts her own sense of personhood. It weirdly recalls the very similar throughline of Emma Stone’s character in Poor Things, only done here without the wit or sharpness or anything approaching the intelligence. It would be stretching a point to say that Poor Things is an attempt to do the same story as The Bride, only properly, but the two films have things in common.

You couldn’t honestly describe The Bride as being a genuinely feminist film in any way, though – Eva’s character isn’t strong enough and the plot resolves itself via a confrontation between Viktor and Frankenstein, the bride herself being essentially passive throughout the climax. It’s arguably another poor decision from a film which is not short of them. The film looks appealing, and has one very effective performance (from Rappaport) but it never feels sure if it wants to be a romance, a horror movie, or a drama, and as a result it just ends up as an insipid blend of the three.

(I’ve just now learned that we seem to be going through one of those occasional periods of heightened Frankensteinian activity, with Netflix producing a new adaptation with Guillermo del Toro at the helm, and Maggie Gyllenhaal directing another new film, apparently to be called The Bride!, with Christian Bale and Jessie Buckley as the two creatures. It will be interesting to see how distinctive and interesting any of these films end up being.)