If you want to get a real sense of how the cinematic landscape has fundamentally changed over the years, you could do worse than look at the box office lists from way back when: films which to a modern eye look like the most campy, cheesy, amateurish pap turn out to have done as well in their day as major studio releases nowadays. Past examples we have mentioned include At the Earth’s Core, which was a top-twenty film in the UK in 1976, and slapped-together Bigfoot docu-drama The Legend of Boggy Creek, which, according to some reports, was #22 in the US chart for 1972.

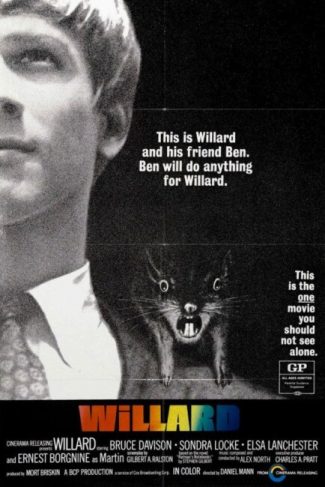

Neither of these films did quite as well as Daniel Mann’s 1971 movie Willard, an extremely odd piece of work which nevertheless inspired a sequel, a remake, and several knock-offs, in addition to launching the career of Bruce Davison. It was just outside the top ten for the year, comfortably outperforming films like Play Misty For Me, The Beguiled, and Shaft. To be honest, this seems one of the inexplicable and bizarre facts orbiting the Willard movies, along with the bit of trivia that the sequel, Ben, features a young Michael Jackson on the soundtrack singing a song about his love for a rat.

This is less of a surprise once you learn that Willard is largely about what happens when a young man becomes a bit too fond of rodents, though it takes a while for this to become apparent. When we first meet him, Willard Stiles (Davison) is an awkward misfit stuck in a bad job at the company his father founded – his father having since died and the business having been taken over by Al Martin (Ernest Borgnine), a crass and ruthless money-grubber. Willard lives at home with his sick mother (Elsa Lanchester) and is seemingly without friends of his own – there’s a cringingly awkward scene early on where he has a birthday party, and everyone there is at least thirty years older than him, invited by his mother.

Still, Willard finds some escape when he forms a bond, of sorts, with the rats infesting his back yard: just one of them to begin with, but rats being what they are, soon there are dozens of the little blighters scurrying about. You have to hand it to Davison – I still think this movie is weird, but in all of the scenes which are basically two-handers between him and a rat, he is clearly taking things seriously. Willard trains the rats to do as he commands and forms an especially close bond with two of them, which he names Socrates and Ben.

This is intercut with the other stuff happening in Willard’s life – most importantly, his mother dies, leaving him the house and a pile of debt, although there’s another subplot about him making friends with a young woman who’s a temp at work (she is played by Sondra Locke, who despite everything clearly eventually figured out that working with Clint Eastwood was a better career move than doing a film about rats). Willard starts taking his rats to work with him, which you just know is going to end badly, while Martin hatches a plan to buy Willard’s family home and turn it into apartments, thus making a fortune. When Martin also engages in a bit of ad hoc pest control at the office, you know that this is going to push Willard too far…

The thing is that while everyone, especially musophobes, seems to agree that Willard is a horror movie, nothing especially horrific happens outside of the last fifteen minutes or so. Prior to this it just plays like a mawkish melodrama about an unhappy young man and the escape he finds through his friendship with the rats. It doesn’t look much like a horror movie – it looks more like high-end TV. In fact, considering the soundtrack as well, it looks most like the kind of live-action film Disney were making around this time. You can almost imagine an alternate Disney-made version of Willard where the rats help him sort his life out and everyone lives happily every after.

However – and, obviously, spoiler alert – it does not play out that way. Willard sics the rats on Martin, who panics and falls out of a window to his death. If this had happened earlier in the movie, you could imagine it as a revelatory ‘now I realise what I can achieve with these rats!’ moment of Willard embracing his destiny as a rodent-themed supervillain (not exactly a crowded field, but it does exist). But the film is nearly over and so, in an apparent moment of contrition, Willard rejects the rats, attempting to drown as many as he can and trying to rat-proof his house. Needless to say he fails, and one night dinner is interrupted by a visit from Ben the rat, who is revealed as an evil rat mastermind who does not forget betrayal. And Ben has company with him…

I’m honestly wondering if the sequel, Ben, isn’t a better prospect as a movie, as the idea of an evil rat mastermind plotting the overthrow of human civilisation sounds more promising than Willard, which plays a bit like Psycho with the horror elements cut down, sentimentality dialled up considerably and a lot more of the money spent on animal training. One wonders if it wasn’t one of these films which inspired James Herbert to launch his horror career with The Rats and its sequels (the actual Willard/Ben knock-offs focused on snakes, spiders and – somewhat more outlandishly – sharks).

The one indisputably good thing about Willard is Bruce Davison’s performance in the title role, as he manages to be fairly convincing even given the most unpromising material. Ernest Borgnine is as good as you’d expect in a very Ernest Borgniney role (the question arises of whether he was cast because he suited the part, or if the part became very Ernest Borgniney simply because Borgnine was playing it). The rest of it is not very distinguished, the main problem really being the pacing – as a horror movie, it takes much too long for anything to happen, and as anything else, the plot takes a hard left turn into rat-attack territory near the end which nothing prior to this point has led the viewer to expect. It’s just clumsily structured and tonally odd – and yet it outperformed some much better films on its original release. It is a funny old world sometimes.